From 1 to 3 April 2025, representatives from twelve nations have come together with a shared mission: to return stolen art and cultural treasures to their rightful, often Jewish, owners.

During the years 1933 to 1945, the Nazi regime looted an incalculable number of artworks and cultural objects across Europe. Behind each stolen piece lies a personal story—of a collector, a family, a life brutally upended. The Netherlands, like many countries, continues the painstaking work of restitution. But this is not a solitary journey. It is a path walked in solidarity, through international cooperation and unwavering moral commitment.

“To prevent the recurrence of these antisemitic crimes, they must carry consequences. This is not easy work. It requires patience, determination, and knowledge. That is why collaboration is essential. To support and to learn from one another.”

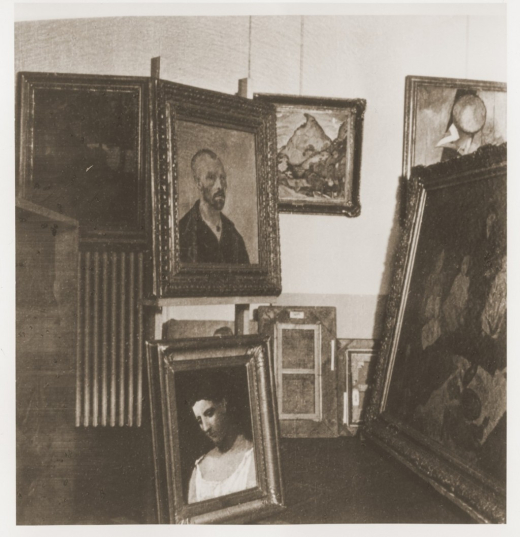

Orphaned Jewish looted art

These days in The Hague are more than meetings—they are moments of reckoning and resolve. Delegations are exchanging knowledge on how to trace and return looted art, visiting the newly opened National Holocaust Museum, and diving deep into discussions on the complex challenges of “orphaned” art—pieces still in public collections, their original owners unknown.

The Netherlands is at the forefront of these efforts. Special attention is being paid to the role of war archives and best practices in handling such orphaned artworks. The Dutch Commission on Orphaned Jewish Looted Art is currently exploring how these pieces might be returned to the Jewish community when heirs cannot be identified—a task laden with historical, legal, and emotional nuance.

The Goudstikker Collection (The Netherlands)

The case of Dutch-Jewish art dealer Jacques Goudstikker is one of the most widely known restitution efforts involving Nazi-looted art. After Goudstikker fled the Netherlands in 1940, a substantial part of his collection was sold under duress or seized during the German occupation. Many of these works were recovered by the Allies and returned to the Netherlands after the war. In 2006, following an extensive claims process, more than 200 artworks were restituted to his heirs. The case highlights both the complexity of post-war restitution and the long-term importance of provenance research.

Gustav Klimt – Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (Austria/United States)

This painting, famously known as the "Woman in Gold", was originally owned by the Jewish Bloch-Bauer family in Austria and was confiscated during the Nazi era. After the war, the artwork remained in an Austrian museum for several decades. In the early 2000s, Maria Altmann, a niece of the original owner, pursued a restitution claim, which ultimately led to a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court. The painting was returned to her in 2006. This case has become emblematic of the legal and ethical challenges surrounding looted art and the evolving international discourse on restitution.

The road to justice may be long, but here in The Hague, the commitment is clear: to restore what was taken, to honour memory with action, and to ensure that the echoes of history are met not with silence, but with responsibility and care.

More about Nazi looted art

Lost Art Database

The Lost Art Database documents cultural property expropriated as a result of Nazi persecution, especially from Jewish owners, between 1933 and 1945 (“Nazi-looted art”), or for which such a loss cannot be ruled out. With the help of the publication of so-called Search Requests and Found-Object Reports, former owners or their heirs are to be brought together with current owners and thus support all stakeholders in finding a just and fair solution.

The Art Loss register

The Art Loss Register is the leading due diligence provider for the art market, and maintains the world’s largest private database of stolen art, antiques and collectables.